The Historical Railway Estate’s (HRE) contractors has completed infilling work on a Victorian tunnel with a tragic past.

The responsibility of finishing a three-month program at Clifton Hall Tunnel in Pendlebury, Greater Manchester was up to AmcoGiffen, whereas the tunnel gained notoriety in the 1950s when the collapse of a construction shaft resulted in five fatalities and four houses on the street above were also lost.

Afterwards, the tunnel was closed and partially infilled but a few voids were left that have now been filled to ensure the tunnel remains safe.

According to HRE engineer Andrew Willison: “National Highways took over managing the HRE in 2013 and had carried out regular safety checks at Clifton Hall.We decided to fill the remaining voids as a precautionary measure and to ensure the site remains safe.”

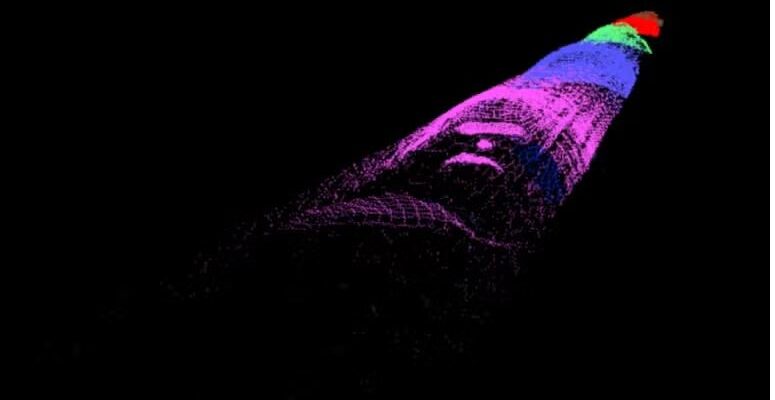

In order to providing 3D images of the voids, AmcoGiffen lowered a cavity auto laser scanner into drill holes before work started.

AmcoGiffen contracts manager Dave Martin said: “The technology was new to the company as there were few scanners in the UK. The imagery helped us to calculate the volume of materials required to fill areas of the tunnel with voids present, one of 200m long and the other 150m long.Both sections had five holes drilled that we used to insert the cavity scanner and to pump the materials during the filling stage. In total 2,200 tonnes of material were needed to fill the voids.”

Considering that cement alone would be too strong and would not flow far enough, as it needed to travel 30m, a mixture of cement and fly ash was used in the voids. Fly ash, made from combusted pulverised coal and added to the cement to increase workability and durability, also meant waste was reduced.

The required time for pumping the materials during the filling stage was 10 weeks, working day shifts to keep noise to a minimum for residents.

The Clifton Hall Tunnel with is a 1,187m length was constructed in 1846 and is a double track horseshoe-shaped tunnel lined with brick and due to that the ground was very unstable where mining had already taken place, its construction was difficult from the beginning. The surrounding area was subject to intense urbanisation. Homes were built directly above the tunnel and there were several rounds of remedial works, including the addition of steel ribbing to provide additional support.

While all trains were stopped and inspection carried out after a partial collapse on April 13, 1953, two weeks later the tunnel roof failed, directly beneath an old construction shaft.

Residents described hearing a loud cracking noise at 5:35am, followed by two houses collapsing. The tragedy resulted in five fatalities and the tunnel was never reopened.