Tunneling is a growth industry outpacing any other construction market. It is estimated at least 50% of the projects worldwide will be delivered using alternative delivery methods including P3 funding mechanism.

Most of the tunneling projects in the United States have been in the traditional methods of design-bid-build (DBB) project procurement; however, in the last 10 years we have seen significant movement toward alternative delivery methods. In DBB the owners engineering firm develops the Basis of Design (BOD) where goals, schedule, budget, design criteria are formalized and documented. The design is then advanced to 100% and approvals and permits are obtained. The project is competitively bid to multiple construction contractors. This contract delivery method provides the most owner control throughout project delivery.

DBB project delivery may be the standard method of procurement and delivery in the United States but overseas alternative delivery in its various forms dominates the tunneling industry. In most of Europe and Asia many major civil engineering projects including tunneling are procured by design-build (DB). Typically, the owner appoints a general consultant (GC) at an early stage and the GC will carry out the initial engineering and design, obtain permits, prepare bridging and tender documents, and act as the construction manager and owner’s engineer. This provides a streamlined service to the owner and a clear point of contact for the contractor.

Over the last few years, we have seen a steady increase in the use of alternative delivery, primarily design-build (DB), led by major city transit initiatives in Los Angeles, New York, Toronto, San Francisco, Seattle and Montreal. It is interesting to note many of Europe’s largest and leading tunnel contractors are winning major projects in North America with alternative delivery procurement, partly due to their experience from Europe and familiarity in handling the higher risk profile and upfront costs involved in bidding DB projects. The two largest-diameter bored tunnel projects in the world, one in the United States and one in Hong Kong, were both constructed with DB contracts and the proposed third largest in the United Kingdom will also be procured using DB.

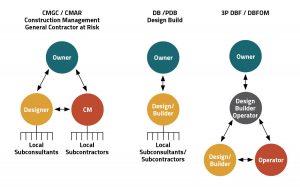

Alternative delivery methods that are becoming more popular in the United States include:

Design-Build: More and more public agencies are turning to alternative forms of contract delivery in order to shorten the time required to implement heavy civil projects. Under this format, the owner or owner’s engineer undertakes compliance with state and federal environmental legislation. A preliminary design is completed and combined with other contractual documentation that becomes the basis for what is normally a two-step design-builder selection process. Under the first step, a shortlist of three or four design-builders meeting the qualifications established in the Request for Qualifications (RFQ) is developed.

The second step starts with issuance of a Request for Proposal (RFP). Included in the RFP are the owner requirements for a preliminary design which may range from 10% to 30% complete. Through this process, the owner seeks to benefit from the innovation that results from close collaboration between the contractor and the owner’s engineer, and to discuss Alternative Technical Concepts (ATC), which helps provide a better design as well as lower cost and risk to the owner.

Progressive Design-Build (PDB): This process allows an owner to select a design-builder based solely on qualifications, agree to a design cost, and then obtain a single guaranteed maximum price (GMP) prior to the start of construction; this is a far less time-consuming method when compared to a conventional design-build format. PDB divides the design-build project into two phases with a single contract encompassing both design and construction. In Phase 1, the preliminary design is completed, the construction plan is set, and establishes the Phase 2 costs to complete final design and the planned construction. This approach allows for the owner to pay the design-builder for final design services and construction work in Phase 2 using Cost of the Work plus a Fee or Lump Sum. Unlike the more conventional design build contract delivery method, the owner does not pay stipends to a competitive field of design-builders. The design-builder holds all the subcontractor contracts and is responsible for scheduling and coordinating their work and their work quality. In this format, the responsibility for design is transferred from the owner to the design-builder. Under this contract delivery method, additional contractual options are available to the owner prior to the start of construction. These options are designed to prevent one party from receiving a windfall in the event the parties cannot agree on the GMP or Lump Sum and the agreement is terminated.

This method of contract delivery developed in the water/wastewater and aviation industries and is migrating to transportation projects. There are very few tunnels completed under PDB. One of the few ongoing PDB tunnel projects is the Silicon Valley Clean Water Tunnel.

Construction Management/General Contracting (CMGC) and Construction Management at Risk (CMAR)

CMGC and CMAR are different terms for the same contract delivery method. In the CMGC/CMAR process the project owner hires a contractor/construction manager based on qualifications to provide feedback during the design phase, before the start of construction. The owner also retains a separate contract for the design engineer who is responsible for preparing the design documents in collaboration with the construction manager. This dual contracting format differs from design-build where a single contract is negotiated for design and construction with the owner. The CMGC/CMAR process consists of two phases. The first phase, the design phase, allows the construction manager (CM) to work with the designer and the project owner to identify risks, provide costs projections, adapt the design to the CM’s preferred means and methods of construction and refine the project schedule. Once the design phase is complete, the contractor and project owner negotiate the price for the construction contract. If all parties agree with costs, then the second phase begins, and the construction manager becomes the general contractor and construction begins. Under this format, the owner retains responsibility and risk for the design. This procurement method is being used for the proposed Enbridge Line 5 tunnel under Mackinac Strait in Michigan, CMGC is also being used for the LACSD Clearwater outfall tunnel from the Carson control plant in Long Beach to the coast at Palos Verdes consisting of a 7-mile, 18-ft diameter tunnel.

Public Private Partnerships (P3)

P3 is a project delivery model that involves an agreement between a public owner and a private sector partner for the financing, design, construction, and often long-term operations and maintenance of infrastructure assets by the private sector partner over a specified term. Under the P3 delivery model, the public owner transfers to the private sector partner risks that are typically retained by the public owner under a traditional delivery model. Long-term operations and maintenance obligations may be included in the contract scope. The degree of risk transfer exceeds that assumed under a design-build delivery model. P3 is a financing model generally used with alternative delivery procurement DB contracts. Variations can include DBF – Design Build Finance, DBM – Design Build Maintain, and DBFOM Design Build Finance Operate and Maintain. In these contracts, the design-builder is asked to finance fully or partially the design and construction. The contractor can be reimbursed in a variety of methods, including milestone payments, progress payment and, availability payments. In DBFOM contracts, finance, operation and maintenance for a set period of time is included in the contract agreement.

The I-75 Segment 3, P3 DBFM Modernization Project

An example of a recent P3 DBFM project currently under construction is the Michigan Dept. of Transportation I-75 Modernization Project (Segment 3) north of Detroit. This project is a Design Build Finance Maintain (DBFM) project with the maintenance period being 20 years and is valued at $1B. This project is one of a few P3 projects with a tunnel in the United States. Others include The Port of Miami Tunnel in Miami, Florida, Hudson Bergen Light Rail and the recently disputed Purple Line in Maryland. In Canada, P3 DBF has become a typical procurement and financing method for transit projects with tunnels in Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa.

Scope of the I-75 Segment 3

The I-75 Modernization Project is located within the road right-of-way for Interstate I-75 north of Detroit, Michigan. The Segment 3 project extends for approximately 5.5 miles and includes adding an HOV lane (the first in Michigan), complete demolition and rebuilding of all bridges, and highway realignment. Much of this section of I-75 is currently in a cut below the surrounding suburban communities and is prone to closure due to deep flooding during storms. At present, the stormwater drainage system is undersized. Water is currently captured from the roadway and adjacent slopes and is conveyed to several pumping stations, which lift the flow to the combined sewers in the adjacent communities, which then also overflow. Included in this project is a 4-mile, 14.5-ft diameter storage and drainage tunnel, designed to be constructed between 40 and 80 ft below the new I-75 roadway. The new system will allow stormwater flows to exit the roadway drainage system by gravity, dropping into the tunnel at seven new structures. The storage and drainage tunnel will then convey the stormwater to a new dewatering pump station.

Financing of the I-75 S3 DBFM Tunnel

The State of Michigan chose the P3 DBFM model for several reasons, including the financial advantages. The DBFM agreement required the developer to acquire financing for the entire capital cost of the project. For the design and construction phase of the project, the state set up a system of milestone payments. For the maintenance phase of the project, the state set up a system of “availability payments.”

To assist in financing the project the state allowed the developer to take a loan from the Michigan Strategic Fund, which also provides tax advantages to private developers working on public projects.

The financing of P3 projects can become quite complex and for the I-75 project the proposing teams had to calculate their bids based on construction costs in the first five years, financing costs plus the 25-year maintenance costs, where the developers had to make assumptions about receiving the milestone and availability payments. The developers then had to source their funds which came from equity partners and bond financing. Only time will tell if the winning team got it right.

The successful development firm, Oakland Corridor Partners (OCP), was formed by the following equity partners – John Laing, AECOM Capital, Dan’s Excavating, AJAX Paving, and Jay Dee Contractors. All the construction firm equity partners were also part of the construction JV team.

As indicated above, P3 financing for projects with tunnels is rare and OCP had 80 days after the contract commercial close to obtain financial close. This required the following actions:

- Obtaining a Bond Rating (“investment risk rating”) for the bonds that would be issued by the Michigan Strategic Fund to raise funds, which were loaned to OCP for financing of the project.

- Convincing investment managers to choose the I-75 S3 Project PABs for consideration in their investment portfolio.

- Choosing an appropriate yield to attract buyers.

- Selling the bonds.

During initial contacts with the bond rating agencies, OCP was advised a P3 civil infrastructure project with a large tunnel substantially increases the risk exposure for the investors.

The tunneling design and construction teams were surprised at the levels of concern raised by the investment communities about the tunnel aspect. Discussions continued and the local experience of Jay Dee as the tunneling contractor was critical in showing how risk could be reduced on the tunnel construction.

The only other P3 tunnel used to compare was the Port of Miami. Reference was frequently made to this project by the rating agencies who were advised how different it was to the I-75 tunnel, with different ground conditions and tunnel size. However, the agencies also referred to recent high publicity TBM failures on projects such as the Alaskan Way tunnel. It was difficult to convince the rating agencies the I-75 tunnel was less risky.

Once the bonds are rated, they need to be managed and underwritten by a bank. The bank arranged for the OCP team to participate in a “roadshow” to investment firms such as Vanguard, Putnam, Fidelity, etc. These potential bond investors also had many questions about the added risk of a tunnel in the project. Their questions revolved around many topics, including the following

- Who is responsible for procuring the TBM, and how standardized is this design?

- How does the current tunneling project compare in complexity to other projects?

- The 14.5-ft tunnel seems unique. What is driving the need [of the tunnel]for this project?

- How risky is the tunnel boring part of the project in terms of a worst-case scenario?

- How complex is the customization [of the TBM]? Are there adequate back-up TBMs if there is a problem with customizing the TBM?

- Why such a long construction period for a project that appears to be mostly road paving and lane expansion with the inclusion of a drainage pipe?

The questions were all answered comprehensively, but it highlights the problem of the tunneling industry with regard to P3 financing. Rating agencies and investors recall the failures, but the vast majority of tunnels completed successfully are not part of the conversation.

For this project, the necessary bonds were all sold successfully and the financial close was completed in the time limit. This concluded the first stage of the project and allowed the construction team to continue with the work that they are more familiar with.

At the present time the new open-face TBM has been delivered to site, completed on-site manufacturer certification, and began the initial tunnel on July 14, 2020. The initial tunnel is due to be completed in mid-November with the trailing gear fully installed.

About the Authors

David Mast is a regional leader for AECOM’s Tunnel Practice, including trenchless technology and underground engineering in North America. He has more than 22 years of experience performing and managing multidiscipline design projects in the water and wastewater industry; design-build projects; rock and soil tunnel design and construction projects and other underground engineering design projects; combined sewer overflow consent decree programs; as-needed geotechnical and environmental services contracts; sewer rehabilitation investigations and repair designs; and geotechnical investigations for municipal, commercial, and retail projects.

Paul Nicholas is the Operations Manager for the AECOM Tunnel Practice, with over 40 years of experience in the heavy infrastructure and tunneling industries. He has a geotechnical background and extensive engineering experience with tunnel boring machines (TBM) in design, manufacturing and operation. Nicholas has worked on tunnel projects in North and South America, Europe, Middle East, India, Asia and Australia and led the successful completions of landmark transit and water conveyance tunnels projects.